It was first reported as a tragic accident when Henry Gein’s lifeless body was found in 1944, lying face down on the edge of the family farm. However, his death is still one of the most perplexing mysteries in American criminal history, even after several decades. Although “asphyxiation by smoke” was listed as the cause in the official report, some of the bruises on his head and the uncanny way his brother Ed led police straight to the body raised disturbing questions that continue to reverberate in discussions of true crime today.

Under their controlling mother, Augusta, who held a strong religious conviction that condemned almost everyone as sinful, the Gein brothers had been raised in emotional captivity. In an effort to encourage Ed to lead a more independent life, Henry, the elder, started to question her extreme beliefs. Quiet and devoted to Augusta, Ed could not fathom disobeying her. Many biographers later characterized the tension between the brothers as dangerously flammable due to their obsessive and unusually intense bond.

The brothers’ routine task of burning off marsh vegetation on their property in May 1944 evolved into something much darker. Firefighters were called in to assist when the fire got out of control. Ed reported his brother missing to the authorities after the fire had died down. However, as though driven by a strange sense of certainty, he chose to walk directly to Henry’s body rather than joining the search. He remained silent and gave no explanation. That silence quickly turned into suspicion among the Plainfield residents.

Table: Ed Gein – Personal, Psychological, and Case Details

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Edward Theodore Gein |

| Date of Birth | August 27, 1906 |

| Place of Birth | La Crosse County, Wisconsin, USA |

| Died | July 26, 1984 (aged 77) |

| Parents | George Philip Gein and Augusta Wilhelmine Gein |

| Sibling | Henry George Gein (died 1944) |

| Occupation | Farm laborer, handyman |

| Known For | Murders of Bernice Worden and Mary Hogan; grave robbing |

| Psychological Profile | Diagnosed with schizophrenia and sexual psychopathy |

| Institutionalized | Mendota Mental Health Institute, Madison, Wisconsin |

| Popular Culture Impact | Inspiration for Norman Bates (Psycho), Leatherface (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), Buffalo Bill (The Silence of the Lambs) |

| Reference | Wikipedia – Ed Gein |

Henry’s clothes were unburned, his head was bruised, and the police discovered his body unharmed by the fire. But in the absence of hard proof or a clear motive, investigators declared it to be an accident. This choice would seem especially foolish years later, when Ed’s heinous crimes were revealed. What had initially appeared to be bad luck started to resemble a terrifying prelude—an early practice of violence hidden behind Ed’s gentle exterior.

Later, criminologists and psychologists examined this instance as potentially a watershed in Gein’s mental decline. According to reports, Henry had denounced Ed’s reliance on their mother as “poisonous.” For a man as emotionally bound to Augusta as Ed was, such words may have felt like betrayal. Some historians have compared it to the biblical story of Cain and Abel, which shows how love, jealousy, and devotion can entwine fatally. In this story, sibling rivalry and divine favoritism lead to the first known murder.

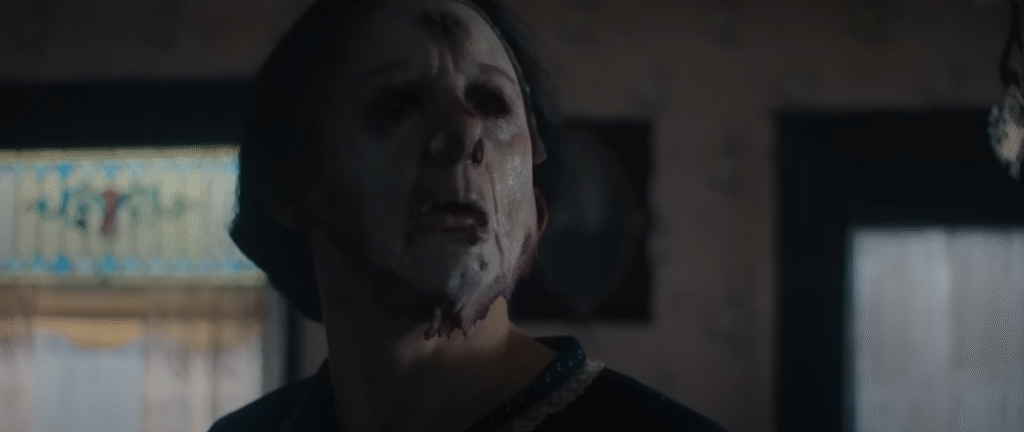

Netflix’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story vividly acted out this theory decades later. Charlie Hunnam’s portrayal of Ed creates a startlingly realistic picture of a man who is suffocated by loneliness, guilt, and delusion. According to the series, Ed’s psychological collapse was sparked by Henry’s death, which was not an accident. The show has significantly rekindled public interest in how brittle human morality can become under the strain of obsession and loneliness, regardless of whether artistic license is involved.

The lack of a confession is what makes the case so unsettling. Ed never acknowledged that he killed his brother. Even under interrogation for the murders of Bernice Worden and Mary Hogan, he avoided the topic, treating Henry’s death as a distant event buried beneath his memories. His frequent return to themes of motherhood, purity, and family, however, raises the possibility that his brother’s passing carried a heavy emotional burden that he was perhaps unable to consciously confront.

Ed took on the role of caregiver for his mother in the years following Henry’s passing. He was left completely alone, detached from reality, and enmeshed in spiritual delusion after Augusta passed away from a stroke in 1945. Desecrating graves, making furniture and masks out of human skin, and killing women who made him think of his mother were some of his later crimes that came from a deeply troubled and tragically lost mind. The tragedy is only made worse by the possibility that his first violent act was carried out by members of his own family.

According to social commentators, Gein’s story illustrates how loneliness and repression can destroy a person’s mental health in addition to reflecting personal pathology. Similar to Jeffrey Dahmer’s delusional seclusion or Charles Manson’s cult dynamic, Gein’s disengagement from society served as a fertile ground for horror. These figures are connected by a strikingly similar thread — emotional isolation magnified by moral rigidity and suppressed desire.

Thanks to Ryan Murphy’s adaptation, Gein has received more attention, which has sparked discussions about ethics, empathy, and how murderers are portrayed in entertainment. While some critics contend that understanding these characters is especially helpful in averting future tragedies, others have questioned whether humanizing them runs the risk of glamorizing evil. Either way, it draws attention to society’s ongoing interest in what makes a seemingly good man into a symbol of evil.

These stories are frequently consumed by contemporary true-crime viewers as psychological riddles, but they also act as mirrors, reflecting our shared attempt to understand moral collapse. When seen in that light, Henry’s death transcends the realm of forensic mystery and becomes a metaphor for the frailty of conscience. If Ed killed his brother, it was not out of hatred but rather from a twisted devotion brought on by a disastrous collision between faith and fear.