When Mary Shelley started writing Frankenstein, she was just eighteen years old. Since then, the book has endured beyond generations, centuries, and even the boundaries of genre. She joined Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and Claire Clairmont at Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816, which is sometimes referred to as “the year without a summer.” Since the group was stranded inside due to the unrelenting rain, Byron suggested holding a competition for ghost stories. The idea of a young woman whose imagination was noticeably ahead of her time served as the impetus for what started out as a playful literary challenge and evolved into a pivotal point in cultural history.

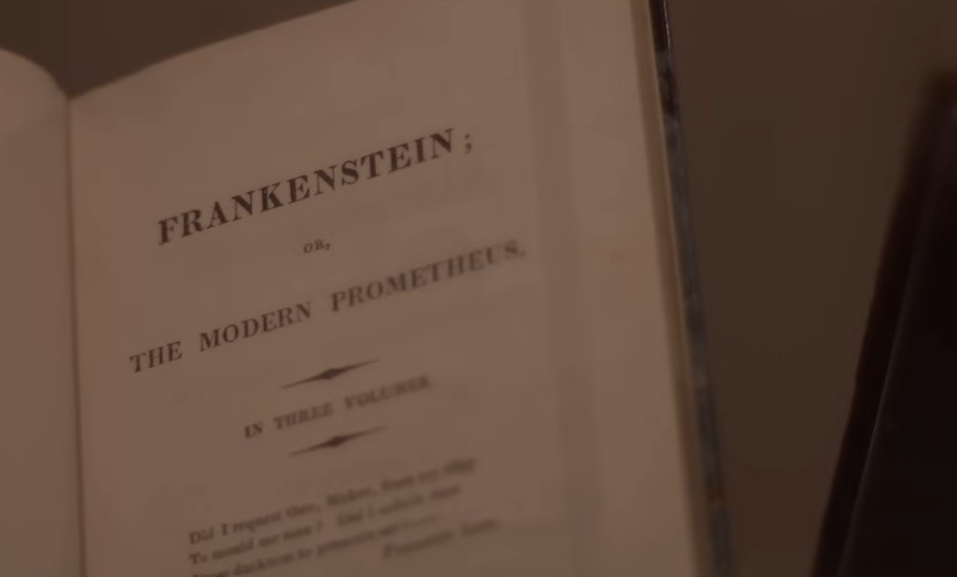

Mary had the idea for the picture that would change literature forever one sleepless night when she was plagued by thunder and electric storms: a pale science student kneeling next to the creature he had just brought to life. Instead of being an idea, the scene appeared to her as a vivid vision that was so eerily reminiscent of a dream that she woke up both inspired and afraid. She started writing the opening lines of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, a tale that challenged the price of creation and humanity’s unrelenting ambition, by morning.

The accomplishment is all the more astounding given her age. Most people are still figuring out who they are at the age of 18, but Mary Shelley was already addressing life, morality, and existence with remarkable depth. She was analyzing human nature, not just conjuring up terrifying images. She had experienced personal heartbreaks and lost her mother at birth, so she had a deep understanding of grief. Every page of her book was infused with that emotional intelligence, which transformed horror into philosophy and thought into contemplation.

Personal and Professional Information

| Category | Information |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (née Godwin) |

| Birthdate | August 30, 1797 |

| Birthplace | London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Parents | William Godwin (philosopher), Mary Wollstonecraft (feminist writer) |

| Spouse | Percy Bysshe Shelley (poet) |

| Occupation | Novelist, Essayist, Biographer |

| Notable Work | Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) |

| Age When She Wrote Frankenstein | 18 years old (started in 1816, published at 20) |

| Authentic Source | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Shelley |

Mary had been prepared by her upbringing, albeit in an unconventional way. Her father, William Godwin, was a trailblazing political philosopher, and her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was an advocate for women’s rights. Both of her parents were radical thinkers. Mary was exposed to complex ideas at a young age because she grew up in an environment of intellectual debate. She read extensively, frequently withdrawing to her father’s library to delve into the writings of Plutarch, Rousseau, and Milton. She had an intellectual foundation that few women of her era could match thanks to her informal but extraordinarily rich education.

She had suffered extraordinary loss before she started writing Frankenstein. At sixteen, she had fled with Percy Shelley, went into social exile, and suffered the loss of her baby. Her understanding of creation and destruction—two major themes that would later characterize her masterpiece—was influenced by these experiences. Her writing turned into a reflection of her life, strikingly capturing the chaos, fervor, and terror that were all around her.

Villa Diodati had an electrifying atmosphere. Science, alchemy, and the nature of life were frequently discussed topics between Byron and Percy Shelley. There was a lot of talk about experiments conducted by people like Luigi Galvani and Giovanni Aldini, who used electricity to make dead tissue twitch. Mary took in these discussions and turned them into artwork. She used storytelling to reimagine what others had debated theoretically. Her depiction of Victor Frankenstein’s experiments encapsulated the tension between ethical concern and scientific curiosity, which is still very much present today.

The anonymous publication of Frankenstein in 1818 led critics to believe that Percy Shelley was the author. Many people found it hard to believe that a woman of eighteen could have written such a profound and terrifying story. She was clearly the author, though, as evidenced by her unique voice, thoughtful structure, and remarkably mature insight. Her husband made some small editorial suggestions, but she was the only one with the genius. She eventually received the recognition she was due when her name was included in subsequent editions.

Her youth was a strength rather than a limitation. Mary Shelley challenged authority at a time when people look for direction. Because it defied convention and combined science, emotion, and ethics into a single story, her writing was especially avant-garde. She portrayed Victor Frankenstein’s creation as both a marvel and a mistake, exploring ambition as tragedy rather than triumph. The novel’s defining strength was its striking balance between awe and caution, which is still very relevant in the era of biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and digital innovation.

Frankenstein’s impact has persisted for a very long time. Its influence grew quickly, from stage adaptations in the 1820s to Boris Karloff’s creature’s cinematic depictions in the 1930s. The monster became a cultural symbol of unforeseen consequences over time, a mirror reflecting the human preoccupation with power. The ageless question of what happens when human ambition surpasses moral responsibility was posed by Mary Shelley at the tender age of eighteen.

Her life and her creation are remarkably similar. She, like Victor Frankenstein, looked to creation for meaning, but not to science but to narrative. However, in contrast to her fictional scientist, she recognized empathy as the essential antidote to innovation. Her writing was profoundly compassionate in addition to being visionary. It warned readers that knowledge devoid of empathy breeds disaster. Personal suffering gave rise to this moral consciousness, which is what gave Frankenstein its universal appeal and emotional weight.

The tenacity of her early brilliance is further demonstrated by her later years. She returned to England after Percy Shelley passed away in 1822, raising their son and writing in spite of financial difficulties. She continued to be an active thinker, wrote novels and travelogues, and edited her husband’s poetry. Her tenacity was truly remarkable; she never let social norms stifle her imagination. She was a woman who was remarkably ahead of her time, even in her quietest years.

Frankenstein’s genius is found in both its story and its beginning. It is especially encouraging that a young woman, surrounded by literary titans like Byron and Shelley, could create a work that was more influential than theirs. It questions preconceived notions about brilliance, age, and gender. In addition to creating a monster, Mary Shelley’s tale is about reclaiming authorship in a society that did not accept the idea that women could create greatness.