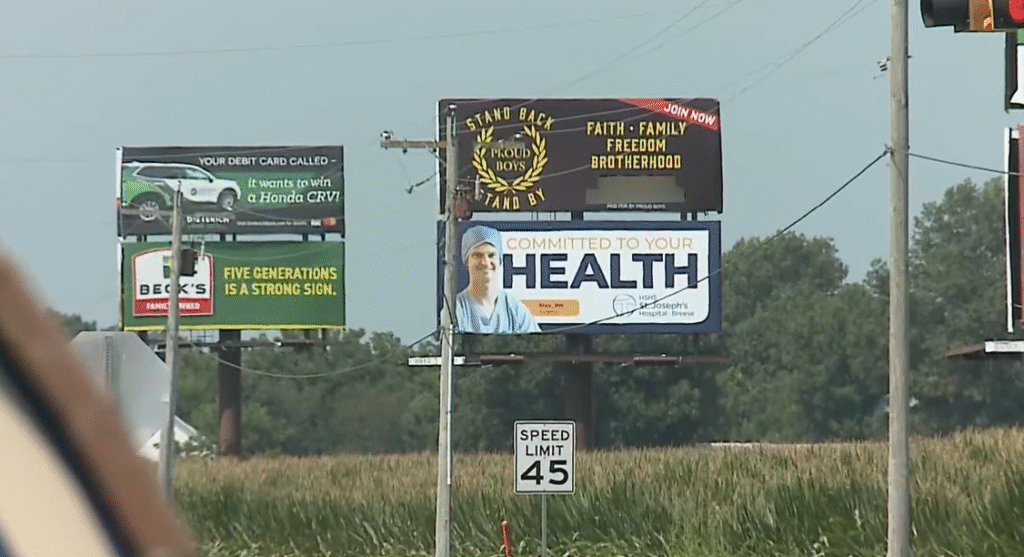

In southern Illinois, the unexpected appearance of a Proud Boys billboard close to Central Community High School started a series of events that effectively demonstrated the strength of group resistance. The billboard with the group’s logo and tagline, “Faith, Family, Freedom, Brotherhood,” was removed in a matter of days thanks to the community’s strong opposition rather than a court order.

Because the sign was less than 1,000 feet from a school entrance, its purpose was very obvious, and locals interpreted it as a recruitment tool for young people. The listed phone number was full, so calls to it went unanswered, but the symbolism was enough to make people uneasy. The Proud Boys tried to raise a flag in a county with close family and community ties. They are frequently linked to the January 6 uprising and have been labeled an extremist group by several watchdog groups. They encountered a resounding rejection, which is remarkably similar to what has occurred in other towns when outside forces try to use public space for polarization.

Nearly 70 people filled the room at a county board meeting, an exceptionally high turnout. During public comment, over thirty people spoke, and their concerns were very evident and their words were very personal. Invoking the 1980s, when the Ku Klux Klan attempted to hold a rally in neighboring Carlyle Lake, former judge Dennis Middendorff emphasized how communities had previously been put to the test. He reminded locals that moral voices could still be heard clearly even though the First Amendment provided protection. He made a very good point: sometimes the most effective weapon is condemnation itself.

Proud Boys Billboard Illinois – Key Facts

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Location | Old U.S. Route 50 and St. Rose Road, near Central Community High School, Breese, Illinois |

| Group Involved | Proud Boys, designated extremist group by SPLC and linked to Jan. 6 insurrection |

| Billboard Message | Logo, slogan “Faith, Family, Freedom, Brotherhood,” local phone number (voicemail full) |

| Public Response | Strong community opposition, 70 residents attended county board meeting, over 30 spoke against sign |

| Legal Context | Clinton County Board had no authority to regulate billboard content but passed resolution condemning hate |

| Removal | Lamar Advertising took billboard down after public pressure, August 2025 |

| Replacement | United Methodist Church rented space for “Hate Divides, Love Unites” campaign |

| Cost of Replacement | $2,100 for four months |

| Wider Effort | Part of church’s broader campaign against racism and extremist messaging, seen in Missouri, Ohio, and North Carolina |

| Reference | Capitol News Illinois |

Teachers, attorneys, and students shared personal accounts of how racism had subtly manifested in public places and schools. Recent graduate Naomi Knapp acknowledged that she was saddened rather than surprised, pointing out that although the majority of people in her town disapproved of such notions, the billboard exposed a prejudice that was hidden beneath the surface. Her words had a particularly poignant resonance because she expressed empathy for any person of color who was compelled to see such a sign close to their school, rather than fear for herself.

The terrifying way extremist groups change their appearance was encapsulated by Black resident Gene Hemingway’s statement to the board, “They’re dropping the robes and putting on suits.” He clarified that although he was alert and cognizant of the danger, he was not afraid. His testimony, which encapsulated the community’s uneasiness in a single line that reverberated throughout the meeting, was remarkably resilient and profoundly symbolic.

Lamar Advertising took down the sign the following day. Although officials claimed they were powerless to control content, the volume of calls and messages that the company received made the decision all but inevitable. The removal’s rapidity demonstrated how pressure, when coordinated and persistent, can be incredibly powerful, greatly limiting the dissemination of extremist messages.

The removal of the sign may have been the story’s conclusion, but the United Methodist Church made sure the resolution would be especially creative. The Church spent $2,100 to buy the space for four months and put up the sign that read, “Hate Divides, Love Unites.” Their choice was not merely symbolic; it was a component of a larger initiative that was being implemented in states like Missouri, Ohio, and North Carolina, where campaigns of a similar nature have been used to combat groups that cause division. Because of this consistency, the campaign was extremely flexible, adjusting to local situations while maintaining its ties to a national movement.

The new sign was incredibly successful in redefining what the community stood for, according to parents like Bucky Miller, who is raising two young children in Clinton County. He claimed that the new message “embodies what our community is all about,” making it abundantly evident that hate should never be excused by family values. His viewpoint illustrated how institutional support combined with grassroots activism produces a very effective plan to retake public space from extremism.

This Illinois billboard battle bears a striking resemblance to larger cultural movements in which campaigns of love and inclusion are used to combat negativity. Artists like Taylor Swift, who has used her platform to speak out against intolerance, and celebrities like Lady Gaga, who has her “Born This Way” Foundation, both exemplify the same idea: replacing divisive rhetoric with messages that promote unity. The Methodist Church’s reaction mirrored that tactic, demonstrating that societies can fight hate by erecting something more resilient in its stead rather than merely demolishing it.

Moments such as these historically reverberate the past. In the 1960s, towns and communities were put to the test as evidence of division frequently surfaced in public squares. The rejection of Clinton County served as a reminder that the heart of America still beats strongest when people refuse to normalize intolerance, and the Proud Boys billboard became a contemporary parallel. The replacement sign evolved into more than just a commercial; it became a cultural icon, demonstrating that communities ultimately control their story, even though extremist organizations may lease space.

The wider effect is remarkably evident. Extremist organizations are putting small towns to the test by hoping for indifference or silence. Silence is no longer the rule, though, as demonstrated in Illinois. Rather, communities are retaliating with amazing effectiveness, frequently substituting messages of compassion for hate. By demonstrating to locals that even symbolic action can have an impact, this proactive approach has significantly increased public trust.