By the beginning of 1854, there was a restlessness in the air in Washington. In Congress, expansion, ambition, and moral debate were crashing into each other like erratic storms. A man who was both feared and admired for his political savvy and keen intelligence, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, came forward with a plan that he thought would ease tensions but instead stoked one of the most intense political fires in American history.

The goal of his proposal, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, was to organize the vast western territories so that a transcontinental railroad could be built and they could be settled. As fast as a locomotive on polished steel, Douglas imagined progress racing across the continent by joining the Mississippi River to the Pacific. But beneath this hopeful outlook was a question that had plagued every generation before him: Would slavery be allowed in new areas?

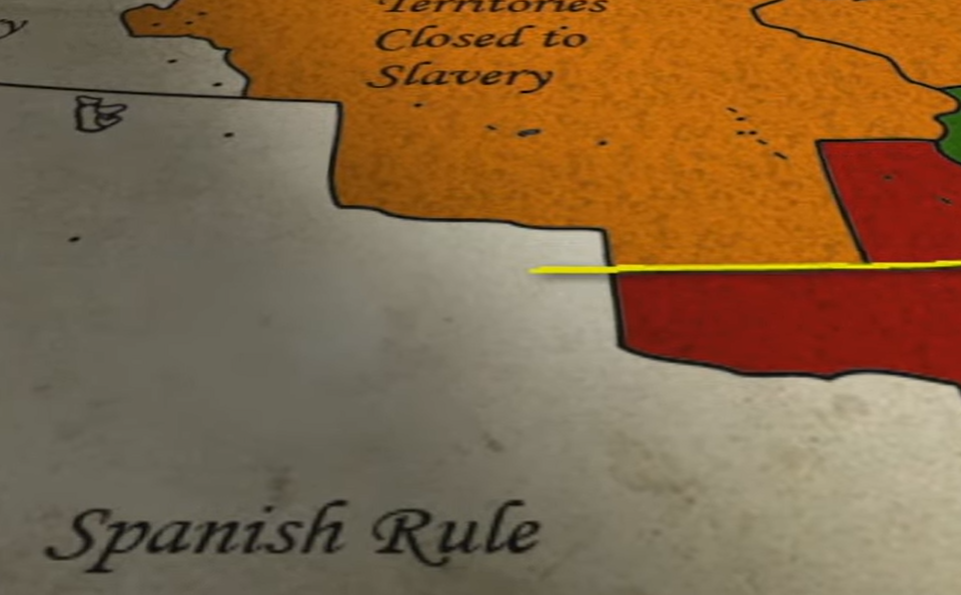

The Missouri Compromise of 1820, which forbade slavery in the majority of western territories, established a clear border at latitude 36°30′. In an attempt to boost development and win southern support for his railroad route, Douglas audaciously suggested that settlers themselves make the decision through “popular sovereignty.” It was an incredibly democratic-sounding but fatally ambiguous concept.

Table: Stephen A. Douglas – Key Information

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Stephen Arnold Douglas |

| Date of Birth | April 23, 1813 |

| Place of Birth | Brandon, Vermont, United States |

| Date of Death | June 3, 1861 |

| Place of Death | Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Nickname | “The Little Giant” |

| Political Affiliation | Democratic Party |

| Notable Work | Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 |

| Major Rival | Abraham Lincoln |

| Reference Link | https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Kansas_Nebraska_Act.htm |

Douglas reopened an unhealed political and moral wound by substituting a fluid vote for a fixed legal boundary. Senators argued vehemently. Southern leaders hailed the act as a victory of state and settler rights, while abolitionists such as Salmon P. Chase denounced it as a breach of sacred promises. Douglas, self-assured and determined, continued. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which changed the course of American history forever, was signed into law on May 30, 1854.

The Missouri Compromise’s prohibition on slavery north of 36°30′ was revoked, and two new territories, Kansas and Nebraska, emerged. While it was an invitation to chaos in practice, it was an appeal to self-determination in theory. Both from the North and the South, settlers flocked to Kansas in an attempt to influence the first vote on slavery. Organized groups of pro-slavery advocates migrated from Missouri, and abolitionists from Massachusetts and other states formed their own resistance communities. The outcome was violence rather than democracy.

Soon after, the area was given the eerie moniker “Bleeding Kansas.” In the name of ideology, families were uprooted, towns were destroyed, and people were killed. Foreshadowing the carnage of the Civil War, the political debate that started in Washington had turned into a real battlefield. When applied to a moral crisis, Douglas’s proudly created experiment of popular sovereignty had shown its perilous fragility.

The effects were severe for Douglas himself. His reputation was once praised as one of the most powerful voices in the Senate, but the chaos his bill caused severely damaged it. Later on, in his debates with Abraham Lincoln, the Kansas question turned into a strategically placed weapon. Asserting that neutrality in the face of slavery was a betrayal of conscience, he charged Douglas with moral blindness. The cries of those suffering in Kansas now made Douglas’s insistence on procedural democracy—”let the people decide”—sound incredibly hollow.

The act destroyed long-standing political alliances. A new movement, the Republican Party, whose guiding principle was opposition to the spread of slavery, emerged when the Whig Party broke up due to sectional strife. The national conversation was reshaped by leaders like William Seward, Charles Sumner, and Abraham Lincoln who capitalized on the moral and political momentum. Douglas, on the other hand, had to tread carefully between voters in the North who hated him and Democrats in the South who mistrusted him.

Without context, it would be unjust to portray Douglas as a villain. Despite his political motivations, he also acted out of a genuine belief in progress and compromise. He looked to democracy to bring unity to a rapidly growing country, but he was unaware that democracy itself was under strain from a moral divide that was too great to cross. His action, which was meant to bring stability to the nation, instead served as a mirror reflecting its most profound divisions.

A striking parallel exists between the Kansas-Nebraska Act and contemporary political gambles that overestimate consensus and underestimate passion. Douglas misjudged how unstable “the will of the people” could become when moral convictions clashed, much like modern leaders who support decentralization or populist decision-making without anticipating its extreme variations.

1854’s lessons are still especially applicable today. When policies based on compromise are in line with common values, they can be incredibly effective; when they are not, they can cause terrible division. In theory, Douglas’ belief in popular sovereignty was a democratic ideal; in reality, it was a spark near dry tinder. Freedom becomes brittle when government fails to fulfill its moral obligations, as the violence in Kansas showed.

In hindsight, Douglas’s action accelerates change rather than just igniting regional conflict. It compelled Americans to face inconsistencies they had previously disregarded. This tension gave rise to new parties, new movements, and ultimately a new national consciousness regarding justice and equality. Ironically, it was the same laws that drove the nation toward division that ultimately led to its rebirth through the Civil War’s flames.