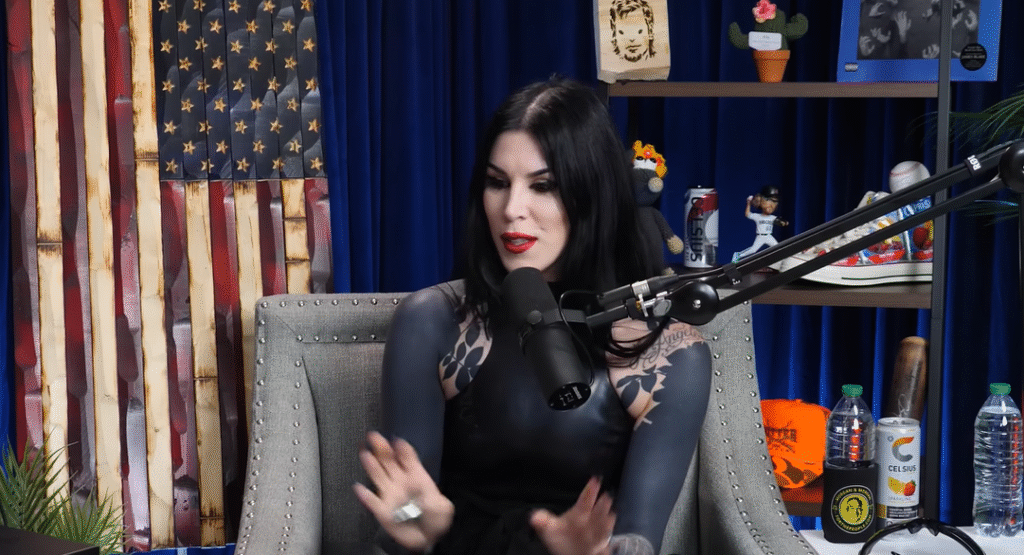

The stakes went far beyond a single tattoo when Kat Von D was called into a federal courtroom in Los Angeles. The focal point of the controversy was her 2017 ink drawing of jazz great Miles Davis on a friend’s arm, which was inspired by a Jeffrey Sedlik photo from 1989. According to the photographer, his copyright was infringed. The lawsuit went right to the core of how artists take inspiration, modify it, and then turn it into new works of art, according to Kat Von D, who has long been considered a pioneer of contemporary tattoo art.

Sedlik’s photograph of Miles Davis is undeniably iconic—stark, moody, and powerfully composed. A vivid reminder of the musician’s mysterious aura, the portrait, which was first published on the cover of JAZZIZ magazine, showed Davis in mid-gesture with a finger against his lips. Sedlik contended in court that his meticulous lighting, setup, and mood-making were not merely incidental, but rather were the core of his intellectual property. He said Von D had successfully copied his work by tattooing the image without his consent.

Kat Von D responded with a defense as audacious as the ink she applied: the tattoo, she claimed, was a tribute rather than a copy. She claimed that it was fair use, characterized it as fan art, and was made for a friend without any commercial intent. She depicted Davis in flowing lines and shaded tones, but her legal team stressed that this was not “substantially similar” to Sedlik’s original photograph. More significantly, no photograph could capture the tattoo’s presence on human skin, a canvas with its own constraints and liberties.

Table: Kat Von D – Biography, Career, and Lawsuit Details

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Katherine von Drachenberg (professionally known as Kat Von D) |

| Date of Birth | March 8, 1982 |

| Birthplace | Montemorelos, Nuevo León, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican-American |

| Profession(s) | Tattoo Artist, Entrepreneur, Television Personality, Musician |

| Notable TV Shows | Miami Ink (2005–2007), LA Ink (2007–2011) |

| Tattoo Shop | High Voltage Tattoo (Los Angeles, opened 2007, closed 2021) |

| Business Ventures | Kat Von D Beauty (rebranded to KVD Vegan Beauty after her departure) |

| Music Career | Released debut album Love Made Me Do It (2016) |

| Family | Married to Rafael Reyes (musician, aka Leafar Seyer) since 2018; 1 son |

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (175 cm) |

| Net Worth (est.) | Approx. $20 million (varies by source, 2024 estimates) |

| Famous Lawsuit | Sued by photographer Jeffrey Sedlik in 2021 |

| Lawsuit Details | Sedlik alleged copyright infringement over Kat Von D’s 2017 tattoo of Miles Davis, claiming it reproduced his 1989 photo without permission |

| Defense | Tattoo was not “substantially similar” and qualified as fair use/fan art |

| Verdict | January 2024: Jury unanimously ruled Kat Von D did not infringe copyright |

| Aftermath | Sedlik’s lawyers signaled an appeal; case sparked major debate on copyright, tattoos, and creative freedom |

| Personal Note | Kat Von D has since blacked out most of her tattoos, saying they no longer represent her life and values |

| Authentic Source | New York Times – Kat Von D Wins Copyright Trial |

In January 2024, the jury rendered a remarkably quick verdict. Within hours, they came to the unanimous conclusion that Kat Von D had not violated copyright. In addition to clearing her, the decision demonstrated how artistic expression can be stifled by strict interpretations of copyright and how creative works frequently build upon one another. The result was especially helpful for tattoo artists nationwide, as it allayed concerns that their art might suddenly turn into a legal minefield.

But this instance is not unique. Courts have been asked more and more in recent years to comment on the fine line that separates infringement from homage. A similar dispute arose for the Andy Warhol Foundation regarding Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, which Warhol had altered in a series of silkscreen prints. In 2023, the United States Supreme Court decided against the foundation, stating that Goldsmith’s original image should be protected even in the face of a well-known reinterpretation. That ruling had a lasting impact, implying that even well-known artists could not arbitrarily use other people’s creations without facing repercussions.

This was the background against which Kat Von D’s case developed. Many were afraid that if she were found guilty, tattoo culture would completely collapse. Consider a tattoo artist who is hesitant to ink a portrait because they are concerned that the reference image may be protected by copyright. The ripple effect would have been significant, potentially leading to higher costs, slower turnarounds, and an erosion of the free-flowing creativity that defines tattooing. The jury’s decision, on the other hand, significantly increased trust in the tattoo community and supported the notion that transformative art can withstand legal scrutiny.

It is impossible to overlook the social aspect of this case. Due to Kat Von D’s notoriety, millions of fans watched the trial in addition to attorneys and artists. With almost 10 million Instagram followers, she unintentionally became the spokesperson for a debate that encompasses much more than tattoos; it also involves music, photography, fashion, and visual culture in general. Her vulnerability struck a chord as she shared updates and talked openly about the stress of dealing with possible damages of up to $150,000. It acted as a reminder that the emotional toll of drawn-out court cases does not spare even well-known people.

The conflict between photographers and secondary creators is reflected in Sedlik’s will to appeal. Photographers make a living by licensing their work; it’s not just a business strategy. They contend that their intellectual work is being diluted when images are used again without their consent. Sedlik emphasized how carefully crafted his photograph was and how Von D’s use of it diminished the value of his licenses to other artists. His team warned that the jury’s verdict could endanger the rights of visual artists, describing the tattoo and the picture as remarkably similar, if not identical in essence.

Von D’s victory also emphasizes how the distinction between art and business is becoming more and more hazy. Her social media posts that featured the tattoo, according to critics, subtly advertised her tattoo parlor and brand. In response, her defense made a very clear point: she wasn’t mass-producing items using Sedlik’s image, the tattoo was a gift, and she didn’t charge for it. The jury ultimately agreed with her interpretation, confirming that not all internet posts are equivalent to being monetized.

The case’s relationship to the societal movement of artists taking back their personal stories is still intriguing. Kat Von D, for instance, has since blacked out much of her own tattoos, spending nearly forty hours covering 80 percent of her body with dark ink. She described many of the older tattoos as “landmarks in dark times” that no longer reflected who she was. Her desire to redefine herself on her own terms, free from outside interference, is reflected in both this decision and her legal journey.

The Kat Von D trial is more than just a single artist’s triumph when it comes to intellectual property. It represents the constant balancing act between freedom and protection, between the rights of artists and cultural development. The message is cautiously optimistic for society: artists can still push boundaries, reinterpret, and learn from one another without constantly worrying about legal action. However, the appeal implies that the story is far from over. Our legal frameworks will continue to be put to the test as we attempt to strike a balance between respecting original creators and encouraging transformative work.