Cities are frequently compared to living things, growing, changing, and sometimes losing aspects of themselves in the name of rejuvenation. However, there is a paradox associated with this change that is especially obvious but frequently disregarded in private. It’s the fine line between gentrification, which replaces, and growth, which revitalizes. The reason the struggle goes unnoticed is not because it is invisible, but rather because advancement can appear incredibly beautiful while subtly uprooting those who laid its foundations.

Urban growth is often presented as a story of triumph. Where pawn shops once stood, coffee shops now flourish, buildings rise gracefully, and streets are repaved. These changes appear to be very positive on paper, offering jobs, safety, and culture. The social equation that underlies these glitzy advancements, however, rarely works out for everyone. As the cost of progress increases annually, long-time residents see their livelihoods subtly squeezed by rising rents and property taxes.

According to sociologist Ruth Glass, who first used the term “gentrification” in 1964, this process reinforces itself. Once the flow of new wealth starts, it picks up speed until the original community is nearly completely replaced. That cycle continues to be remarkably effective decades later, transforming cities like Austin, London, and San Francisco into dazzling showcases of economic expansion—and sobering reminders of cultural loss.

There is more to this unseen conflict than just economics. It has to do with belonging. Identity becomes a commodity as once-affordable neighborhoods are rebranded as “emerging markets” and art districts turn into real estate goldmines. The weight of profit erodes the sense of home, especially in historically marginalized areas. Geographer Neil Smith’s rent gap theory provides a clinically precise explanation of this: developers focus on areas where the gap between potential and current value is greatest. That gap turns into a threat as well as an opportunity.

Profile – Peter Moskowitz, Author and Urban Researcher

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Peter Moskowitz |

| Profession | Journalist, Author |

| Notable Work | How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood |

| Focus | Urban development, inequality, and displacement |

| Nationality | American |

| Source | https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/537726/how-to-kill-a-city-by-peter-moskowitz/ |

Growth, however, is not always bad. It improves amenities, makes streets safer, and revitalizes abandoned neighborhoods. Significantly lower crime rates and better access to healthcare have been observed in many gentrifying neighborhoods. These results are seen by city planners as confirmation that their investments are effective. The hidden cost, however, is in how this change reinterprets who benefits and who belongs, as Community Frontline pointed out in its study. For newcomers, progress can feel especially good, but for those who are already there, it can become excruciatingly exclusive.

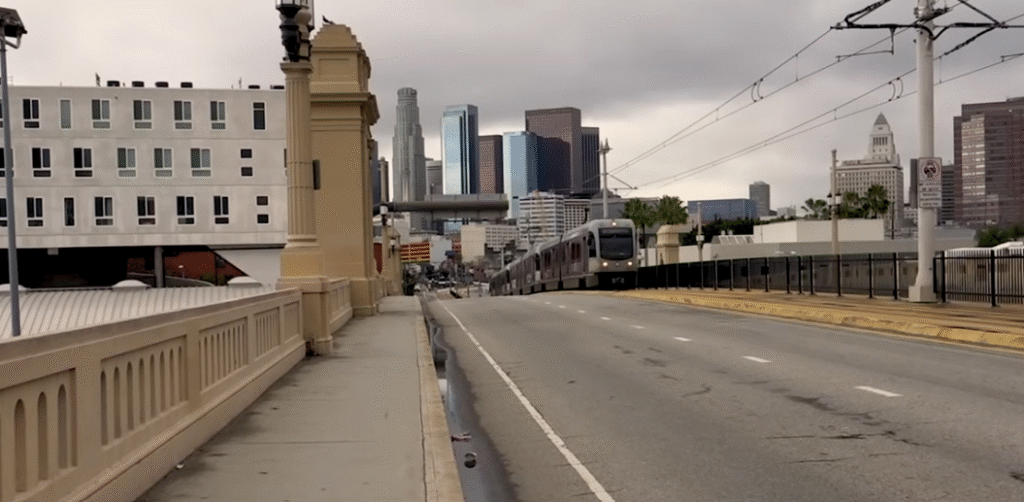

This dichotomy is frequently embodied by cultural leaders and celebrities. The attention brought excitement—and price inflation—when Beyoncé and Jay-Z made real estate investments in New Orleans. Longtime Latino residents were displaced when creative professionals relocated to Echo Park in Los Angeles, revitalizing the neighborhood. Ironically, the very authenticity that draws investment is frequently what disappears first in every city.

Data rarely captures the psychological aspect as well. Gentrification often starts with subtle alienation rather than eviction for many families. A beloved eatery closes. A barber in the area loses his lease. A more subdued, sterile beat takes the place of the neighborhood’s well-known rhythm. People are driven out by fatigue, a gradual loss of familiarity and comfort, not by animosity. Thread by thread, the social fabric is being replaced by carefully chosen aesthetics that seem less human and more transactional.

This change is indicative of a larger cultural trend toward the commodification of space in general. Cities’ strategies become increasingly effective at luring talent and investment as they vie for international recognition, but they become less successful at maintaining diversity. Municipal campaigns use slogans about innovation and renewal, while real estate companies promote “creative quarters.” Behind those campaigns, however, are locals battling growing expenses and constricting spaces—people witnessing their memories being priced out block by block.

This is frequently referred to as “the soft violence of progress” by urban sociologists. It’s a slow reevaluation of who gets to stay rather than an outright act of displacement. The smell of the neighborhood bakery is replaced by the sterile aroma of boutique coffee, the faces shift, and the languages wane. Despite its beauty, progress occasionally destroys more than it creates. However, it also teaches resilience. In response, many communities are implementing especially creative models, such as community-owned enterprises that maintain equity at the local level, cooperative housing, and trusts for cultural preservation.

Some cities have begun to realize that development cannot be sustained if it excludes people. By stabilizing rent and reducing property taxes, Portland’s Community Benefit Agreements and Philadelphia’s Land Bank seek to safeguard local citizens. Despite their flaws, these policies are a step in the right direction. Urban planners are starting to view fairness as infrastructure—a foundation as necessary as steel or concrete—by incorporating social equity into zoning and housing decisions.