From being a little-known medical term, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, has become one of the most hotly contested conditions in sports and neuroscience. It is a degenerative brain disease brought on by repeated head trauma, including subconcussive and concussive, which gradually changes the structure and function of the brain. These effects trigger a cascade of tau protein misfolding, which spreads throughout the brain and kills neurons, according to research. The fact that this illness cannot be conclusively diagnosed until after death is what frustrates physicians and families the most.

Table: Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Overview

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy |

| Abbreviation | CTE |

| First Described | 1928, by Dr. Harrison Martland (“punch-drunk syndrome”) |

| Causes | Repeated head trauma, concussions, and sub-concussive impacts |

| Main Symptoms | Memory loss, confusion, aggression, impulsivity, mood swings, dementia |

| Diagnosis | Definitive only after death via autopsy (tau protein buildup in brain) |

| Affected Groups | Contact-sport athletes (football, boxing, hockey), military veterans, abuse victims |

| Risk Factors | Early exposure to contact sports, number of impacts, genetic predispositions |

| Treatment | No cure; supportive care for symptoms, therapy, lifestyle management |

| Research Centers | Boston University CTE Center, Mayo Clinic, NIH studies |

| Reference | Mayo Clinic – CTE Overview |

Nowadays, athletes are the most well-known examples, with their hardships frequently brought to light long after their careers are over. The tragic declines of NFL legends Aaron Hernandez and Junior Seau, who were both later found to have suffered from CTE, shocked fans. Their examples demonstrated symptoms that were remarkably similar amongst people: depression, aggression, impulsivity, and eventually cognitive decline. The illness does not differentiate based on celebrity; it has been observed in both college athletes and Super Bowl champions, indicating the pervasiveness of the dangers associated with contact sports.

CTE’s effects are not limited to athletes. The symptoms of military veterans exposed to explosive blasts have been remarkably similar to those of football players, indicating a shared vulnerability linked to repetitive trauma. The condition has been linked to people with histories of repeated falls and survivors of domestic violence, demonstrating the disease’s wide-ranging effects. As demonstrated by these cases, CTE is a public health issue as well as a sports-related one.

The majority of what we currently know about CTE was developed by Boston University researchers under the direction of Dr. Ann McKee using brain donations from athletes and veterans. According to their research, hundreds of NFL players who were posthumously studied had evidence of the illness—a number that was much higher than previously thought. This information has compelled organizations and leagues to face harsh realities. Soccer, the NFL, and the NHL have all had to admit risks, adjust procedures, and provide funding for studies. The way that contact sports are played and governed has changed, and these modifications, albeit small, are especially creative.

Often, CTE symptoms start out mildly. It can show up as impulsivity, irritability, or unexplained mood swings in younger people. Memory loss, disorientation, and dementia become more prevalent as the illness worsens. Numerous families talk about a loved one’s “changing personality,” a painfully irreversible and intensely personal metamorphosis. As an illustration of how devastatingly silent the progression can be, when news of Rudi Johnson’s death broke, conjecture centered on mental health issues and potential connections to CTE.

Will Smith’s role as Dr. Bennet Omalu in the movie Concussion, which chronicled the discovery of CTE in former Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster, increased Hollywood’s visibility. Public consciousness was remarkably shaped by that cultural moment. Parents of young athletes started to raise concerns about the dangers of early contact sports exposure, which sparked discussions at community meetings and school boards. By bringing medical science into homes, the narrative made sure that the discussion was no longer limited to locker rooms or scholarly journals.

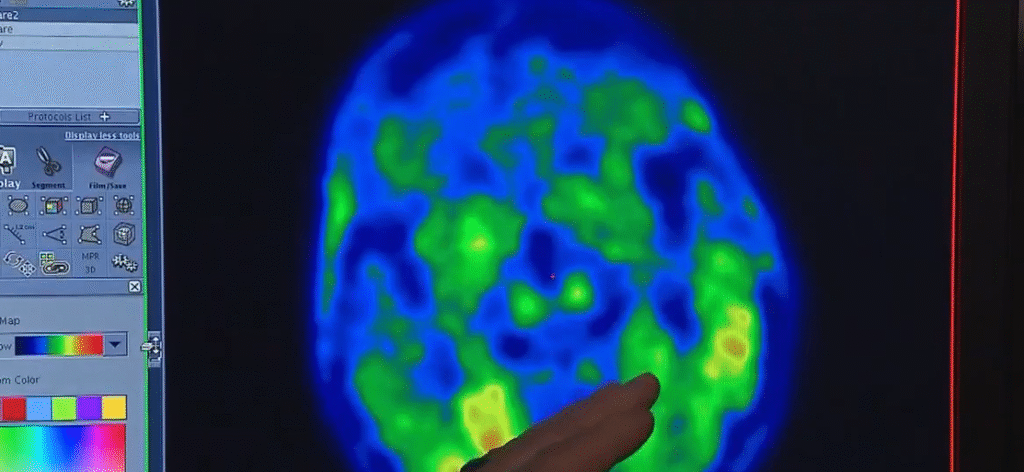

Lifetime diagnosis continues to be the most difficult. The only way for doctors to determine whether a patient has “probable” or “suspected” CTE is to combine their symptoms and medical history with the results of other tests. Though not yet validated, biomarkers and advanced imaging are being tested. Without definitive answers, families are frequently left in agonizing uncertainty as they watch a loved one deteriorate. However, supportive treatments can be especially helpful—quality of life can be significantly enhanced by lifestyle changes, therapy for mood disorders, and organized daily routines. These treatments show that care can still have a significant impact even though they are not curative.

The financial ramifications have also been significant. Sports league lawsuits have cost billions of dollars, and insurance premiums for youth sports organizations have increased dramatically. Impact sensor-equipped helmets, head-contact-limiting training programs, and even AI-powered monitoring to monitor cumulative trauma are all being developed by companies. Despite their great effectiveness, experts warn that technology cannot take the place of prevention. Cutting down on impacts is the only incredibly obvious solution.

The debate over CTE has changed the cultural definition of toughness. Playing through a concussion was once viewed as heroic. Taking a player off the field for assessment is now regarded as a responsible act of care. From Lady Gaga to LeBron James, celebrities have contributed to the discussion by emphasizing brain health in advertisements and interviews. Although their advocacy takes place outside of the sports world, it shows how this condition affects people far beyond athletes and shapes how people in various communities and professions perceive brain injuries.