The courtroom no longer felt like a sporting contest on the seventh day of testimony. It was more akin to the gradual unraveling of years of stress, skillfully concealed beneath courteous remarks made after races and smiles at racetracks. The relief in racing circles at the announcement of the settlement was remarkably reminiscent to the sensation following a near-miss collision.

The case itself was remarkably illuminating. NASCAR was accused by two teams, 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports, of retaining monopoly control through a charter system that promised stability but gave the league nearly all of the strength. Many owners silently disliked the dependency created by the contracts, which were renewable but never permanent, even if they continued to sign.

Charters operated like golden tickets with an expiration date for almost ten years. Teams never completely owned their position on the grid, despite spending millions on vehicles, buildings, and employees. When NASCAR proposed updated charter conditions with a midnight deadline in September 2024, the disparity became very apparent. Although it was never explicitly stated, the message was very apparent.

Sign today to avoid racing unprotected.

The majority of teams complied. Two didn’t.

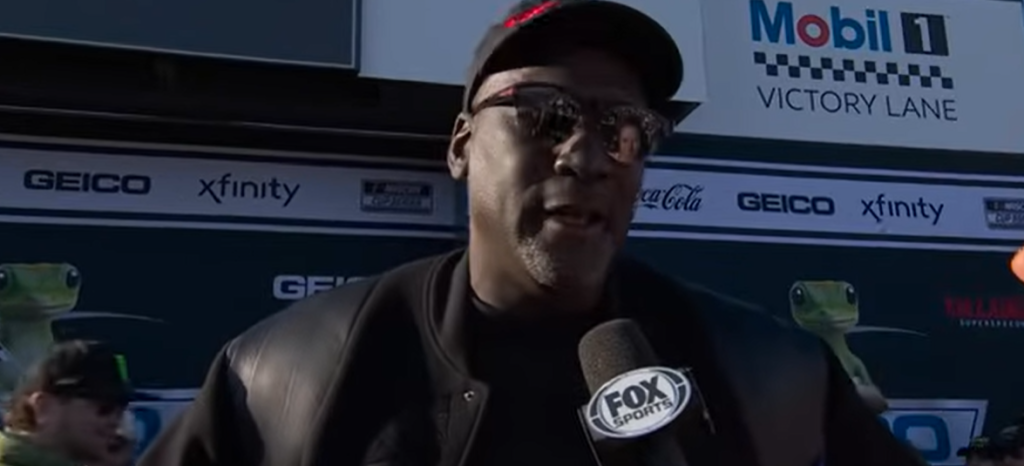

The moment Michael Jordan got involved, the atmosphere changed. He wasn’t loud or dramatic, but in a way that few owners could match, he was financially independent of NASCAR. His decision to advance was especially novel in a system based on tacit acceptance because he did not require the sport to thrive.

The case claimed that competitive freedom had been severely curtailed by NASCAR’s control over entrance, revenue distribution, and sourcing regulations. Teams described vehicles prohibited from competing abroad, contracts that felt less negotiated than imposed, and uniform parts that could only be bought from approved sources.

Longtime proprietors testified about being constrained by deadlines and rules that reduced their options. One person likened the procedure to standing on a trapdoor and negotiating. That impression persisted, particularly when emails and letters came to light, exposing years of secretly smoldering resentment.

The timing was crucial since the settlement was reached before a jury could render a verdict. As lawyers carefully worded it, NASCAR agreed to make charters permanent, or evergreen. This was especially helpful for teams, since it transformed a brittle permission slip into a durable asset that could be transferred, sold, or leveraged.

Additionally, revenue sharing was significantly enhanced. Teams were able to access more revenue from media, intellectual property, and even foreign expansion. The building now more closely resembles a partnership than a toll booth, which the owners feel is necessary for long-term viability.

NASCAR maintained control of the sport’s associated racing series, tracks, and governance at the same time. Ownership remained with the France family. There was no asset sale. From a league standpoint, this result was incredibly successful in safeguarding the organization while resolving its most vulnerable areas.

According to reports, Judge Kenneth Bell forewarned both parties that further legal action might tear down the foundation that keeps the sport together. His worry wasn’t only theoretical. A jury decision against NASCAR might have led to years-long appeals, which may have forced asset sales or changed the rules governing private racing series.

When one owner talked about signing prior charters while feeling squeezed, I paused and reflected on how infrequently that kind of discomfort is visible to the public.

NASCAR used tradition and loyalty to bridge structural divides for many years. However, handshake economies are no longer relevant in current racing. Expenses have increased dramatically. The state of sponsorship has become more unstable. Teams require stability for long-term planning, hiring, funding, and pride.

That equation is altered by permanent charters. They are now considered durable assets by banks. Investors are able to more clearly model risk. Once-trapped owners now have something concrete, highly adaptable, and transferable.

Avoiding a legal precedent was equally crucial from NASCAR’s perspective. In privately operated sports leagues, where centralized authority, exclusive regulations, and spec parts are typical, a courtroom defeat would have had repercussions. By reaching a settlement, NASCAR managed the problem without drawing further attention.

The trial’s emotional toll is still present. Relationships were destroyed, according to emails. Old wounds were reopened by testimony. After all, racing is a personal affair. Slights are more memorable to people than balance sheets. However, compared to the previous structure, the one that emerged from this conflict seems incredibly dependable.

Jordan’s involvement needs to be interpreted carefully. This was not a petty lawsuit or a celebrity flex. It was a well-thought-out decision based on business reasoning and decades of experience in leagues where teams more fairly distribute risk and reward. Despite the high stakes, the tone of his approach was surprisingly reasonable.

For smaller groups, the result is very important. In contrast to continual innovation, stability has significantly increased, providing a clearer route for survival. Although it is less obvious to fans, the difference is significant. Deeper competition, more reliable lineups, and fewer abrupt departures are all signs of a healthy squad.

The idea that teams are stakeholders, not just participants, is something that this settlement subtly normalized, and it may be remembered more in the years to come than the legal spectacle. Even if it is small, that change is quite effective at averting future hostilities.