Few courtroom dramas over the last 20 years have so clearly outlined the future of voting rights as Ohio’s voter identification cases. For the grassroots coalitions that rallied behind them, the clash between civil rights lawyers and state officials transpired in ways that were remarkably affordable and remarkably clear in intent.

Subodh Chandra and his legal team at Chandra Law Firm began challenging Ohio’s recently passed voter ID law on constitutional grounds in 2006. Their main contention was that the law disproportionately hurt voters of color and those who were homeless and had difficulty obtaining the necessary documentation, a worry that is remarkably similar to that expressed in states like Georgia and Texas.

Chandra and Sandhya Gupta offered a particularly creative legal strategy by drawing on their years of experience in civil rights litigation. They demonstrated how poll workers could, whether on purpose or by accident, disqualify valid votes by concentrating on both the practical implications and the wording of the statute.

Bio Table: Key Legal Figures in the Ohio Voter ID Challenge

| Name | Role | Organization | Notable Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subodh Chandra | Managing Partner | Chandra Law Firm LLC | Filed multiple suits challenging voter suppression | chandralaw.com |

| Sandhya Gupta | Voting Rights Lawyer | Chandra Law Firm LLC | Advocate of the Year for voting rights | chandralaw.com |

| Algenon L. Marbley | Federal Judge | U.S. District Court (Ohio) | Issued key rulings against restrictive ID laws | fjc.gov |

| Gregory L. Frost | Federal Judge (retired) | U.S. District Court (Ohio) | Initiated hearings on TRO against voter ID | fjc.gov |

| Marc Elias | Democratic Lawyer | Elias Law Group | Opposed GOP-backed voting laws in multiple states | eliasonlaw.com |

| Mike DeWine | Governor | State of Ohio | Signed stricter voter ID laws into effect | ohiogovernor.gov |

| Joseph Deters | Prosecutor | Hamilton County | Launched investigation into voter ID-related conduct | ohioattorneygeneral.gov |

Judge Gregory L. Frost was given the case at first, but it soon became urgent. Because of its links to previous allegations of unequal access to voting machines in 2004, it was reassigned to Judge Algenon L. Marbley within 48 hours. With Marbley’s well-established knowledge of the subject and his keenly analytical grasp of voter suppression strategies, that move was incredibly effective.

Judge Marbley halted portions of the ID law with a temporary restraining order during the initial hearing. For absentee voters, whose ballots had already been cast under less restrictive guidelines, his decision was especially advantageous. But the state swiftly filed an appeal, and the Sixth Circuit granted a stay, exposing the profound political divisions within the legal system as well as between state agencies.

Intricate court orders, consent decrees, and judicial clarifications ensued, which significantly lessened voter confusion, especially during early voting periods. An order from 2008, for example, made it clear that absentee ballots could not be disqualified for simply not including an ID number—a mistake that is frequently brought on by unclear form design rather than voter misconduct.

Chandra Law made headlines throughout the lawsuit for thwarting efforts to invalidate thousands of provisional ballots, particularly in districts where African-American candidates were expected to win important contests. These legal actions had an instantaneous, quantifiable effect on local elections and were not merely symbolic successes.

Judge Marbley’s decisions became models of fairness and urgency, particularly those rendered in the days preceding elections. The Secretary of State issued an order during the 2012 election cycle to reject some provisional ballots because they lacked identification. Judge Marbley quickly overturned the order, holding that voters shouldn’t be denied the right to vote because of a poll worker’s mistake.

Despite criticism for changing procedures so close to Election Day, these last-minute interventions held up very well in court. The majority of Marbley’s rulings were maintained by the appeals process, reaffirming the idea that inconsistent or deceptive regulations cannot limit voter access.

Financially, the courts granted more than $2.6 million in legal fees to civil rights organizations. Despite its size, this number demonstrates the extent of community-based organizations’ opposition and the level of institutional involvement required to preserve voting rights.

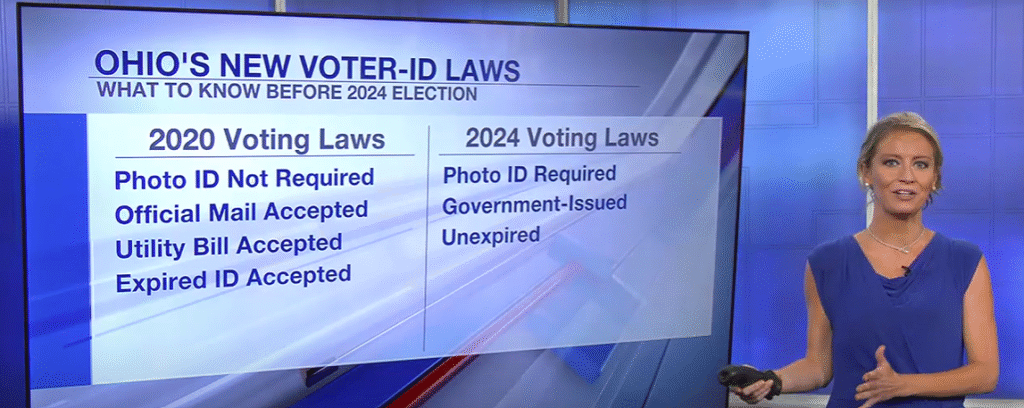

The argument didn’t go away in the years that followed. Indeed, tensions were heightened in 2023 when Governor Mike DeWine signed another voter ID bill, leading individuals such as Marc Elias to declare the law unconstitutional. Using the same precedents set by Judge Marbley and the NEOCH litigation, legal teams prepared challenges once more.

Through initiatives such as “Vote Early, Vote Big!” Subodh Chandra worked with transportation coalitions and Black churches to establish a movement that went well beyond the courtroom. By encouraging thousands of African-American voters to cast their ballots early, the program significantly increased turnout and lessened traffic on election day.

Ohio’s voter ID lawsuit has gained national attention in recent years. When Stacey Abrams started Fair Fight in Georgia, she pointed to the drawn-out legal battle in Ohio as evidence of how restrictive laws can persist through convoluted, slow court proceedings if they are not immediately repealed.

Public personalities have also taken center stage. Ohio native LeBron James openly supported voter access programs. In districts where voter ID laws have historically had an impact, his nonprofit, More Than A Vote, provided funding for initiatives to educate and transport voters.

The Ohio example provides a road map for early-stage advocacy groups: integrate public education, political pressure, and legal knowledge to revolutionize electoral access. The way the legal strategy combined case law with real-time data collection and testimony from voters who were denied the right to vote was especially creative.

These advocacy teams increased their impact and refuted claims that voter ID laws are innocuous by forming strategic alliances. They showed how marginalized groups could be disproportionately affected by even small administrative requirements.

The end of an era was marked by Judge Marbley’s 2017 decision to dissolve the original 2010 consent decree, stating that the statute and litigation had addressed its goals. But it also demonstrated that only through persistent, well-coordinated effort were those objectives accomplished.

Ohio’s legal past will be a litmus test in the upcoming years as more states tighten their ID requirements. It demonstrates that although laws are subject to change, their effects must be continuously examined in court, in policy, and through active civic engagement.

1 Comment

Pingback: Is War Spending a Necessary Evil or Just National Addiction? - Kbsd6